The Safety Car appeared for the first time in F1 in 1973, during the Canadian Grand Prix at Mosport. At that time, the organization of the Grand Prix was not as rigorous and standardized as today, whether in terms of safety or otherwise. Each organizer did his own thing. Following an accident involving François Cevert, the "pace car", as it is called in North America, intervened by jumping in front of the second driver rather than the leader, disrupting the lap by lap and making the classification confusing, sowing doubt about the latter for a long time. The experience had scalded everyone.

Subsequently, we never saw a safety car neutralize a race again (outside America) until the early 1990s, while the 24 Hours of Le Mans had already been using the pace car since the 1930s, before adopting the safety-ar in 1981. It was only from 1993 that the Safety-car was officially introduced, first in F1 before becoming widespread in other non-American automobile disciplines.

On the other hand, Refueling has been commonplace in Grand Prix since the latter existed, except when it was not necessary during periods when, with small and less thirsty engines, shorter races and more resistant tires than modern slicks, teams saw no benefit in saving a few Kg of fuel between stops. The few seconds gained by lightening the F1 cars during each stint did not justify wasting a lot of time in the pits to refuel and change tires. Work on the cars was much slower then than it later became when refueling was reintroduced in 1982 by the Brabham engineer Gordon Murray.

But with FISA's desire to control the escalation in power of turbo engines in F1 in the mid-1980s, the simplest and most effective solution to achieve this was to reduce consumption, which implied ban refueling, starting in 1984.

However, these two elements, the “Safety Car” and refueling, would return in F1 from 1993.

Why did this happened?

- The context:

At the beginning of the 90s, after the ban on turbos, F1 experienced a major technological leap, first with the introduction of the semi-automatic transmission, then this accelerated with the active suspension (which allowed the Williams-Renault team to dominate the competition), synthetic fuels, fly-by-wire controls, traction control, four wheel steering... but these spectacular advances ended up harming the show. Only the richest teams could afford to develop these technologies, crushing other teams and making races more or less predictable. At the same time, it was the time when Eurosport channel began to broadcast the american CART championship by satellite, in Europe in particular, which allowed the European public to get an idea of the quality of the show on the other side of the the Atlantic and therefore could not help comparing it to F1.

To drive the point home, following a season dominated by his Williams-Renault where he won the world champion title in the summer, Nigel Mansell was nevertheless unable to renew his contract with his boss Frank Williams under the conditions that he considered it consistent with his new status. Hurt in his self-esteem, he preferred to emigrate to the USA to race in Indy as several other ex-F1 drivers before him did with great success.

His thunderous and victorious debut in this championship in 1993 propelled the CART audience in Europe to a level threatening the popularity of Formula 1. It was at this moment that Bernie Ecclestone, then F1 big boss, sensed the danger and decided to act in collaboration with the new president of the FIA, his friend Max Mosley to counter the American offensive.

It was obvious that Indycar was a well-established spectacle and above all well mastered, and that F1, due to its cosmopolitan, open character and increasingly dependent on large automobile companies, willingly sacrificed spectacle and sporting balance in the name of victory at all costs and technological excellence of which F1 considered itself to be the supreme and exclusive showcase.

To match the INDY, if not surpass it in the eyes of F1 fans who were also gradually taking the path followed by Nigel Mansell, the FIA chose the simplest solution: Imitate CART.

Starting by banning all the latest technical innovations and driving aids (with the exception of the semi-automatic transmission which was very advantageous in terms of reliability, and therefore costs).

Then, it was the return to refueling banned since 1984, which were a spectacle in themselves in America, where they help to spice up the races and shake up the rankings to the delight of American spectators eager for Hollywood-style twists and turns. , however artificial it may be.

Together with refuelling, another major innovation inspired by the USA was introduced: the safety-car, just like the American pace car.

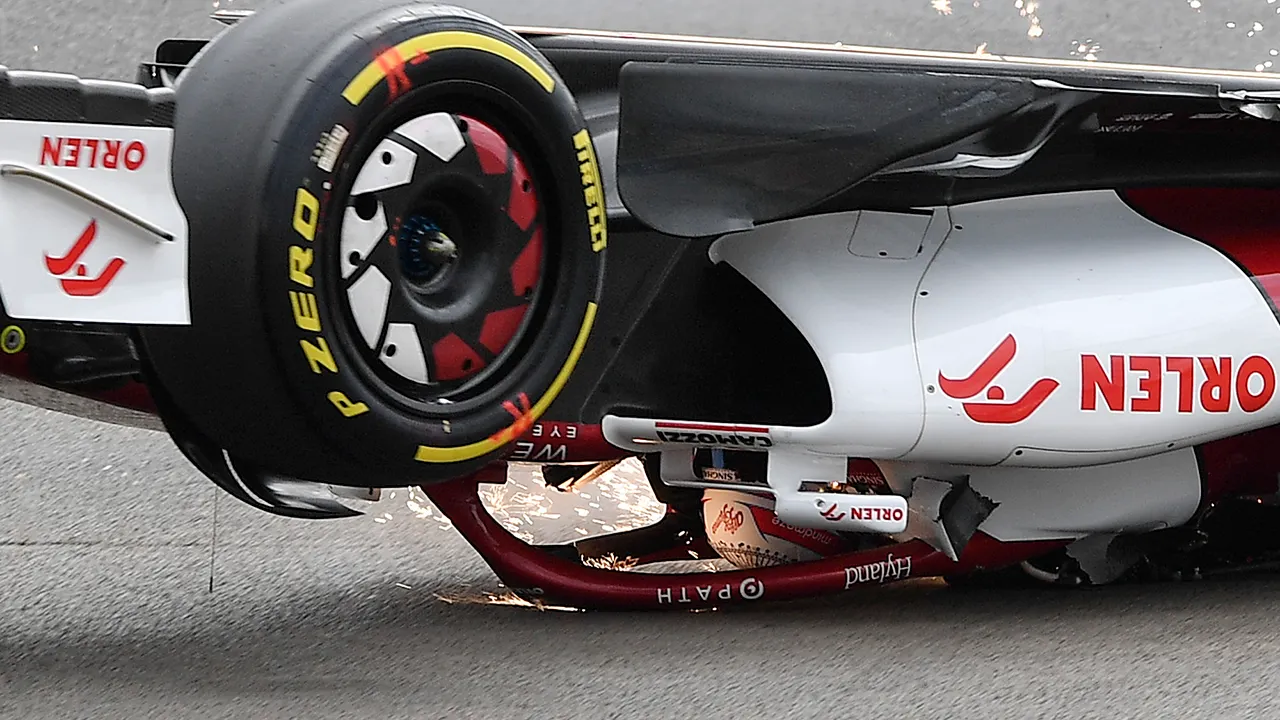

These radical and hasty changes naturally required time to adapt. This was not without missteps, and sometimes even dramas (more or less serious accidents and fires in the pits during refueling and tire changes...), although the effect on the show could be felt, even if this was largely outweighed by several factors.

Indeed, these modifications had arrived at a time when a usually outsider team, Benetton, was beginning not only to seriously threaten the domination of Williams-Renault, but also to dominate the series, in part thanks to its extremely talented and ambitious driver, Michael Schumacher, to his engineers...and also thanks to a somewhat free interpretation of the regulations probably encouraged by the rather cavalier boss of this team, Flavio Briaore. A new era of domination was to be feared to the point that the FIA had to intervene on several occasions to put a spoke in the wheels of these new scarecrows in order, among other things, to maintain interest in the championship.

Finally, over time, refueling and the safety car definitively became part of the customs of F1. But refueling had become so controlled that it made the races largely predictable, to the point that overtaking (if we can call it that) was done much more in the pits, namely during refueling stops and tire changes, than on the track. This often ends up giving rise to high speed processions, notably on certain circuits like Barcelona (which the teams know so well from running there during the off-season and during private tests, to the point that spanish or Catalunya Grand Prix are regulated like a routine flight plan with almost no risk taking on track or surprises).

Worse still, following a typically European and elitist trend of seeking absolute performance and perfectionism, pit stops in F1 had become so perfect to a point their duration was reduced to such an extent that the spectator could see nothing more than an ultra-fast and precise mechanical ballet, which repeated without improvisation or imponderables - with rare exceptions - ended up becoming commonplace.

Part of the effect originally sought (spectacular and unpredictable refueling) was no longer there. The irony is that this ended up harming overtaking which became more rare. Almost everything now came down to stopping strategies. Strategies that are predictable and often known to everyone! Because in the era of easy access to information, thanks to new media and information technologies which provided Grand Prix commentators with a wealth of live detailed information on the racing strategies of each team, even before race starts, the public could no longer be surprised by unforeseen events. Spectators and commentators ended up wishisng each time that the rain would come and mingle with the show, just to spice it up and redistribute the cards.

In dry conditions, drivers talent became secondary, it was the entire team that decided the result. Certainly this has always been the case in motorsport, but in general, the work of the team was made before the race, whereas during it, it was on the shoulders of the driver that the race rested largely. That was at least the case for Grand Prix racing, unlike endurance, for example.

The permanent radio contact ended up driving the point home to the point that the engineer can now dictate almost every action to the driver, leaving him little room for improvisation.

- Why didn't it work as planned?

In fact, in its desire to imitate CART, F1 tried to adapt American solutions to its sauce. This ended up giving the opposite result to that sought. If copying was necessary, it would have been better to do it intelligently. In Indy or NASCAR for example, the number of mechanics intervening during stops is limited, therefore the intervention is longer, giving rise to more possibilities of errors, hesitations and other unforeseen events in addition to making the pit stop visually telegenic. In F1, the camera can barely capture a piece of the car because there are so many mechanics around it! We also see the Indy or NASCAR driver making signs and talking to his team, communicating... in short, it's more interesting and more... human. Sometimes even funny... :)

Ultimately, these refuelings were banned from F1 again after less than two decades when it was realized that they had a large part of the responsibility for the poor spectacle that F1 had achieved. The official excuse was safety and cost... well costs in terms of spectators lost in favor of INDY probably...

For the safety car, then, the problem was not to copy the Americans badly, but rather to have copied them altogether.

In the USA, the conception of a sporting event is different from the rest of the world. Americans love interruptions during a game, and some of the specifically American sports are characterized by these very frequent pauses. We see it in Baseball, Ice Hockey, American Football... and also in car racing, especially in the most popular categories. Interruptions are an element of american culture and media, fundamentally motivated by an economic objective dear to uninhibited and aggressive capitalism: to be able to insert as many advertisements as possible and encourage spectators to consume beers and other popcorn and chips or coke cans during the neutralizations.

As a result, the interventions of the pace car are a godsend for the sponsors and indirectly for the organizers and participants who recognize the merit of indirectly filling their bank accounts. The pace car also has a safety advantage, but specific to racing on ovals.

Racing on an oval circuit is precisely a question of rhythm (hence "pace" in pace-car). The cars drive on ovals at a sustained and very fast pace. All just a few centimeters from a threatening concrete wall. Breaking this pace with simple yellow flags at the accident site would be dangerous. You do not brake on an oval without risking causing a pile-up because on this type of circuit you rarely and briefly touch the brakes, this requires great concentration and a lot of finesse and anticipation to avoid making any movement abrupt, especially since a turn passes quickly. This means that after an accident, it is out of question to simply slow down the accident zone with yellow flags. This would introduce a certain danger zone where cars would be forced to brake and then restart afterwards, thus introducing chaos into the rhythm of the field, especially given the lap times, and distances required for slowing down and restarting on such circuits (most of which are very short), the momentum will be broken for at least half of the lap disrupting the race in any case.

Finally, on an oval, there is practically no respite time allowing emergency services to intervene, the cars pass constantly given their often high number compared to the distance of the circuit, and because of the very short lap times, not to mention the fact that overtaking outside the yellow flag zone during intervention would be too dangerous since these overtaking maneuvers also require a preparation time and distance which can sometimes take an entire lap given the speeds reached and the short lenghts of the circuits.

So, the idea emerged of introducing the pace-car to contain the cars during the race, a pace-car which was already used for flying starts in Indianapolis, but for this time to dictate a regular rhythm to the entire peloton in the event of an accident and not only before the start during the warm-up or parade laps.

Afterwards, it was a matter of tradition that the pace car was extended to racing on American road circuits. But there was also another reason for this which had already proven itself...

As luck would have it, it very quickly turned out that aggregating a stretched peloton was the best way to restart a long NASCAR or Indycar race which was getting bogged down in monotony and possibly break the dominance of certain competitors. This could only please a North American audience too accustomed to last-minute tricks and twists like in Hollywood films. The average American spectator has no problem with artifice (as in all areas of his daily life), as long as it gives him his dose of adrenaline, even if it is to the detriment of the credibility of a scenario or sporting fairness. The participants, for their part, have been used to it for generations and never think to question this situation, however unfair it may be, especially since it also has a significant economic advantage as specified above.

Finally, the interests at stake in an American race are not as important as in an F1 GP, and the manufacturers are aware that this is part of the the game and that it pleases their public. Moreover, if no competitor dominates the others, precisely thanks to this system, then almost everyone can win one day or another. Perhaps they have also understood for a long time that winning all the time is not necessarily a good thing for a company's brand image. They are the kings of marketing after all...

- What about the European copy of the Pace car?

As we have seen, the safety goal of this process is fully justified on an oval, and its extension to American road circuits was certainly a question of habit and the search for spectacle at all costs so dear to the Americans as well as a guarantee of additional money coming in which was very pleasing to the various sponsors and therefore to all those involved in these championships.

The argument of artifice in the service of show was probably the main motivation of Bernie Ecclestone and the FIA to save F1 from the monotony which threatened it at the time of the domination of Williams-Renault. But with the big industrial stakes in F1, this new measure was not popular among top teams, which did not prevent the most influential members of FOCA from accepting it reluctantly, also aware of the threats weighing on their sport which required a rapid reaction.

The public also had difficulty accepting this change which distorted the sport in their eyes. The worst case scenario occurred when a race ended under a yellow flag. The spectators largely prefer the case of a race being stopped and amputated for example of its last 5 or 10 laps rather than seeing the latter accomplished behind the safety car, or to see the latter disappear before the last lap to restart a race which would be played entirely on a single lap or turn, perhaps distorting the result and possibly allowing the least deserving to win thanks to a daring overtake or an unfair hazard or strategy improvisation. We saw the controversy that such a situation caused at the end of the 2021 Formula 1 season in Abu-Dhabi.

The worst was when the SC became generalized to other races with a shorter format. Imagine the frustration of a spectator who buys his ticket expensively and also travels hundreds of km to attend an FIA race lasting 20 or 30 minutes per round and who sees the last half (10 or 15 minutes) completely neutralized under safety car. Even worst: the same thing could be repeated in the 2nd round if the circuit lends itself too much to crashes and pile-ups like some city tracks, or in the event of capricious weather!

Unfortunately, this has already happened several times, like in WTCC. We haven't seen anything more insulting to the public (apart from the 2005 Indianapolis F1 GP of course).

The safety argument does not hold water on a road circuit, especially since the lap times are quite long and the pelotons are thin (as is most often the case in several championships to whom this imported process is imposed). In those cases emergency services can intervene in complete safety while being sufficiently protected by yellow flags. For more safety, officials could even show these flags 400 meters before the yellow flags zone and some 300m after for example to avoid the slightest risk. Strict respect for these flags should be sufficient.

There remains the risk of lack of visibility in the event of rain, threatening marshals and drivers safety in yellow flag areas, like what caused the fatal accident of Jules Bianchi. It is clear that in such conditions, neither yellow flags nor even the safety car are sufficient. Interrupting the race immediately is the only thing to do, even if it means restarting it later.

But as we know, considerations other than the participants and rescuers safety push some organizers to favor interests and firmly locked contracts (in the case of televised races).

In other cases, such as when the safety car intervenes at the 24 Hours of Le Mans for a very localized accident while the circuit is more than 13 km long, this remains inexplicable if not purely a phenomenon of mimicry which is reinforced with time, or by the fear of being reproached for not having blindly applied this safety rule in the event of an unlikely serious accident occurring in the yellow flags zone... unless it is a pretext to restart a long soporific race. Fortunately, this is not systematically the case for the slightest accident occurring during another big endurance race, the 24 Hours of the Nürburgring! In that race at least, common sense is preserved despite the dangerousness of the track.

The security argument to defend the safety-car is therefore rarely credible. Not surprising. As we have seen, the primary reason for its introduction was completely different... always the same... "Follow the money"!

.235ba4da.jpg)

.jpg)