The problem of racing drivers' heads vulnerability has been around for a very long time. After the deaths of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger in 1994, the FIA imposed side protection around the cockpits. Nothing more had been done in this area for a long time despite the occurrence of several serious incidents affecting this critical part of the drivers' anatomy, apart from the introduction of the HANS system. It was not until the accidents which cost the lives of Jules Bianchi at the Japanese Grand Prix and Henry Surtees in Formula 2 that the subject was raised again.

The choice of the halo for F1 and then its generalization to other categories of modern formula cars was imposed after several tests and discussions which sparked lively controversies between security "progressives" and purists. In the USA, the same problem arose after several serious accidents where drivers were hit in the head. But the Americans' choice ultimately fell on the Aeroscreen, a sort of windshield leaving an opening at the top to allow the driver to get out (shall we conclude that closed racing cars like prototypes and hypercars are dangerous and must now be opened to facilitate the exit of the driver in the event of an accident where the doors are blocked? well, we know that the constraints are not the same, the structural requirements of a single-seater are different from the characteristics of wider and more heavy race cars, and what poses a problem in single-seaters is not really a problem elsewhere... but can we ignore the fact that getting out a driver from a closed race car after a crash has proved many times to be problematic? what is tolerated in GT or Touring racing is apparently not in single-seaters...).

However, many fans believe that the "halo" distorts the aesthetics of the single-seaters and would limit the visibility of the drivers, which they believe could harm their safety. This last argument was quickly brushed aside by a number of drivers themselves, most of whom have sincerely (or out of professional obligation?) recognized that it only requires a short time of adaptation and that afterward it is hardly noticed. If they say it, we can only believe them. After all, they are capable of racing in torrential rain with near-zero visibility if their contract requires them to do so. And it is difficult to see them collectively accepting a measure that would clearly call their security into question.

As for the other argument of the opponents of this system, aesthetics, it is defendable even if one can object that in this case, it is the public which quickly gets used to it, as with everything else. We must also recognize that aesthetically, the designers have done a very good job of integration to the point that modern F1 cars (and I'm only talking about F1 cars) still remain quite beautiful with the halo, which is less the case with Formula 4 cars for example (but who cares about F4 look after all?). Better anyway than the Indy Cars whose shape of the Aeroscreen breaks the line of the car with their flared look.

Despite the controversy surrounding the halo in its early days, the FIA stood firm and eventually imposed it against all odds - notably purist spectators - arguing that the sport is evolving and that conservatism and tradition should not be preserved to the detriment of security. Which leads us to the following reflection: Why do the defenders of the halo readily agree to distort single-seaters in the name of safety but do not consider covering, for example, the wheels of these same single-seaters in the name of the same principle?

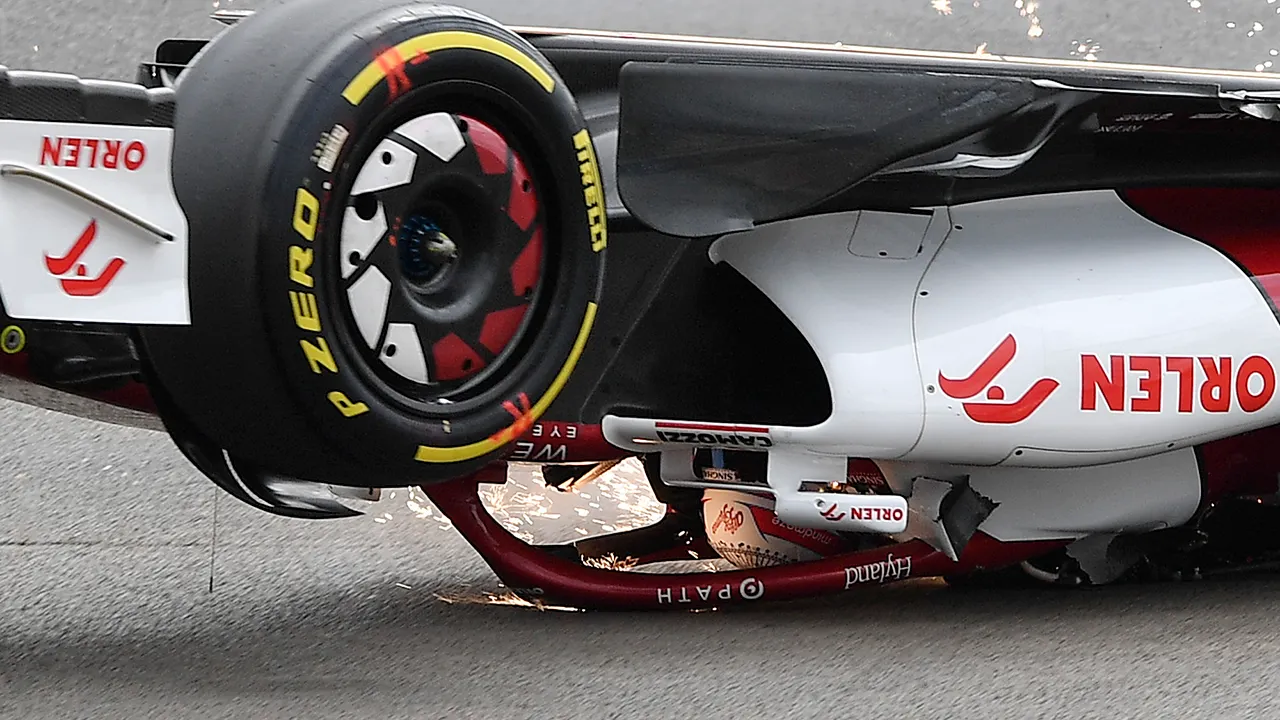

They are very progressive when it comes to the halo, but conservative when it comes to the visibility of the single-seater wheels! The wheels on the outside have, however, often represented a danger in the event of an entanglement between cars, in collisions where the single-seaters climb over each other and fall into dangerous postures, or when the wheels become detached or suspension elements break and hit drivers, marshals or spectators.

Prototypes and other closed racing vehicles are safer in this respect precisely because they have covered wheels. Even if it means making the single-seaters unrecognizable with the "Halo", we might as well go all the way by covering the wheels and suspension elements, if we take safety seriousely. This can only have a beneficial effect and save lives.

Many articles and videos have come out recently to demonstrate that the halo has not only saved several lives, but that it would have saved many more in the past if it had existed. Even if this demonstration is based only on speculations unfounded by irrefutable facts, we cannot deny that the halo or the aeroscreen in Indy still played a certain role and perhaps saved a few lives or careers, even if we will never know in what proportion. Statistically, the accidents of the past where the heads of the drivers were dangerously exposed and where they found themselves a few centimeters from the wheels, the guardrails, the ground, the walls or the fence posts, tend to demonstrate that the halo would not have make a big difference. Often the rollbar, in the case of rolling for example, played its role quite well, and luck did the rest in other situations. At least most of the time. And yet, during most of the history of racing, there was neither a HANS system nor side protections in the cockpits...

There is no doubt that the effectiveness and probability of saving lives of this innovation will increase over time, but not to the extent that we are led to believe.

The same arguments could be made for covering the wheels on the outside. Except that no one is proposing it... let us recall in this regard the fatal accident of Marco Campos in F3000 in 1995.

An accident which eloquently demonstrates as much the danger of open cockpits as of uncovered single-seater wheels. The inconsistency of the federal authorities on this point, by caring about one aspect but not the other, is puzzling...

If we can make an effort regarding the cockpits, why not do it for the wheels? Covering these is much less restrictive for the driver than imposing the halo after all. And for the spectator, it is enough to give him some time to adapt his eyes... Safety first, right?

Single-seaters with covered wheels were well known at one time in North America. The famous F5000 rebodied and renamed CANAM towards the end of the 70s and beginning of the 80s. Visually they were spectacular even if a little clumsy (but this was mainly because of their enormous air intakes and a poor old style "boxy" design).

Even today, in club races in the USA, there are very beautiful single-seaters with covered wheels and the public seems to appreciate them. Visually, however, they remain spectacular.

Origins of a tradition:

It must be understood that this original aspect of single-seaters (outside wheels and open cockpit) is a heritage from the beginnings of automobile.

In the beginning the cars all had this appearance (driver and passengers uncovered and external wheels just like horse-drawn carriages), and it remained this way for several decades. The basic compartment or hood appeared shortly after to cover the passengers from bad weather and wind, and the wings above the wheels, supposed to protect them from splashes of water, stones or mud, were simple mudguards. These were therefore not structures forming an integral part of the bodywork.

Moreover, when motor racing started shortly after the invention of the car, it is logical that the competitors, for reasons of practicality and lightness, only took on board the minimum. This philosophy of the pure radical racing car remained of course and was retained for the top racing series in particular, Formula 1, and by extension and pragmatic spirit also, for all the lower formulas. This is what made the single-seater as we know it.

This almost minimalist look of the single-seater is so rooted in automotive culture that modifying it by covering the cockpit for example or the wheels can only provoke a reaction of rejection from fans. Certainly, motor sports are inevitably destined to evolve, it is the very nature of the industry and the technology which are the basis of the automobile, but if it means daring to do so for one element (the cockpit), why stopping there?

This leads us to question the true motivations of the most zealous legislators when they engage in selective securitarianism. In terms of zeal, the latter is generally only expressed after one or more serious incidents. In short, this zeal is mainly there to respond to an emotional reaction. It is clear to anyone who carefully observes the sequence of events that lead to such decisions that what motivates them are often political considerations, the fear of incurring criticism for inaction, and therefore of taking responsibility for them, legally and financialy, particularly on subjects as sensitive as drivers safety. Especially since when technically credible solutions to this problem are put forward publicly, it is difficult for the legislator to ignore them without solid counter-arguments.

We must also not forget the financial aspect which comes into play. Having knowledge of the existence of these security measures, insurers for their part do not refrain from putting pressure on them, failing which they are no longer prepared to compensate in the event of an accident considering that the first parties concerned (organizers, teams, drivers) did not do everything that could reasonably be done to guarantee the safety of the drivers.

Without forgetting the interests of the manufacturers of these devices (when there are any, like the HANS system) or the inventors who own the patents and lobby at the federal level to impose their findings... The Aeroscreen has been skillfully suggested, taking advantage of a live transmission of an INDY race, by the company which already had it in its plans and which had experience in the field of fighter plane cockpits. In short, opportunism to open up a new market.

These pragmatic and unaltruistic considerations explain the fact that paradoxically, this zeal is generally absent from more anonymous competitions, where this type of innovation only spreads after a long period. As in all areas of public life, media coverage and public opinion play a preponderant role in political decisions, which means that we see no or very few such radical reactions in matters of security in the lower less popular series, or in those which are publicized but without attracting a large audience, and even more so if they do not benefit from live transmission, such as rallies and hill climbs which remain to this day much more dangerous than races on circuit.

Serious accidents is those races make less headlines in the media, and the general public is not interested in them, apart from the minority of petrolheads who accept in advance the risks inherent to racing. This is what legitimately leaves the public, particularly purists, with a feeling of hypocrisy with regard to certain very advanced safety decisions in high-level motorsport.

This double standard makes it appear that federal authorities value life in a discriminatory manner. This feeling is all the more obvious when we think of road safety problems which are treated with much less severity and urgency. Driving rules, the granting of driving licenses, passive safety above all and to a lesser extent the active safety of production cars and road infrastructure, do not benefit from the same exclusive attention. Which raises questions about the priorities of the FIA, the legislators and the manufacturers.

Some legitimately believe that the emphasis on safety in elite motorsport is disproportionate to efforts to improve the safety of production vehicles. But that would be to forget that it is much easier to take care of the safety of a few dozen drivers for limited periods of time (limited time of competitions) than of hundreds of millions of vehicle users around the world. On the other hand, one could not reasonably expect that production cars would all be equipped with roll-bars or require passengers to wear helmets. Economically this would also not be viable, although with economies of scale it is always possible to reduce costs to some extent. There remains the feasibility and practical side of things.

On the other hand, we are entitled to wonder if so much energy and means invested in motorsport to maximize safety are justified, in addition to the additional costs borne by the participants (in the cases of generalization of these costly and restrictive measures to lower categories), ultimately resulting in a marginal safety gain.

This leads us to raise the problem of adapting these security solutions to inferior formulas. We know that if they were planned for F1 or Indy for example, it is on the basis of extensive tests and data specific to these elite Formulas.

Take the HANS system as an example. Its development was based on the study of the forces exerted on the necks of drivers of very high performance vehicles. Knowing that this accessory has a prohibitive acquisition cost, imposing it on drivers in amateur races where the forces experienced are far from those for which the HANS was developed is unnecessarily costly. Even more so when it has to be replaced if it has been damaged in an accident to the point of making its reuse ineffective according to the standards set by the FIA. There is also the problem of homologation which require the regular renewal of this type of accessories and the cost that goes with it.

This question is not always relevant, however. For example, we have seen terrible accidents occur in inferior racing formulas with very limited performance where more drastic measures would have had to approach those of F1 to hope to avoid serious consequences. We think, for example, of a certain accident where an F4 driver had his feet amputated following a head-on collision with another stationary car, exactly as was the case for Alex Zanardi who was driving in Indycar at a much higher speed on an oval.

In short, it would be appropriate to study the relevance of these solutions for lower categories on a case-by-case basis. Their adoption should also not be an additional financial barrier to access to motorsport to the point of making it even more elitist than it already is.

We must not forget that whatever we do, motorsport will always be a dangerous sport. It would be more relevant to put aside bad reasons when making safety choices, and to avoid excesses which are never good. Making sweeping decisions based on isolated incidents to appear to be taking action is not a good thing.

It is important to find a balance between driver safety and the essence of motorsport. A more sincere, permanent and courageous reflection on the relevance of these measures and their overall impact is necessary to guarantee safety while preserving the beauty of the spectacle and the authenticity of the sport. On the other hand, tradition in motorsport is an important point to preserve, but we must not forget that it remains a subjective and relative point of view, and that the sport always ends up changing in a perceptible way or not. This said, those changes must not affect historic races at least...

Finally and above all, we would still like to have the same uncompromising concern for the lives of road users even if economic considerations tend to make this objective difficult to achieve. Otherwise, in the long term, we risk a shift towards a situation where the gap between the importance given to a handful of racing stars and that given to a majority of racing drivers and road users would leave an impression of unjustified elitism. It should be remembered that the drivers have nevertheless chosen of their own free will a high-risk sport which only involves their own lives while the road user, especially when it's only a passenger, didn't make this choice...

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment